There's a very interesting (if entirely wrong-headed) article over on Slashdot right now, and an even more interesting comment thread again.

It's essentially the classic Luddite argument brought back yet again: increasingly smart automation is going to make all human employment obsolete. We'll have robots not just to grow food and make cars but "flipping burgers, cleaning your house, approving your loan, handling your IT questions, and doing your job faster, better, and more cheaply."

The implied questions are "will this happen?" and "will it matter?", and the answers are "it's been happening for centuries" and "not really, no".

An interesting place to start with this is America in the early-to-mid-20th century, in which the Luddite argument was frequently re-framed in a positive way. Industrial automation, it was expected, would essentially kill 'work'. People wouldn't have to work 40 hours a week. They'd barely have to work at all. Robots would do all the work, leaving people to laze about and have fun.

Now, an interesting question: has this happened? You might, at first, be tempted to say "no". Most people still have full-time jobs, after all.

I'd argue, however, that on a deeper level the answer is "yes", it's just not immediately obvious. Furthermore, it's something that's been happening for much longer than is often recognized; really, throughout human history.

We can just abstract the question to one of the basic attributes of humanity, one of the things we consider to define an 'intelligent' species: tool use. We use tools. Why? To increase the efficiency of our labor.

Let's take the most basic, cliched example imaginable: knives. A knife's a tool. What does it let us do? A human with a stone knife can kill an animal more easily. They can eat a dead animal, or most other types of food, more easily. They can construct shelter more easily.

So: it makes their labor more efficient.

Let's throw 20th century political thinking back to the stone age: did the introduction of stone knives render stone age humans unemployed and lead to massive social problems? Well, no. It meant stone age humans had to spend less time and effort killing animals and cutting up food and constructing shelter. So it meant rather more of them didn't die in inconvenient ways, and gave them a bit more time to do things like get around to inventing *more* tools.

And so we fast-forward, extremely damn quickly, to, let's say, the middle of the last millennium or so.

Somewhere around there - it'd be interesting to pick an example society and try and pinpoint roughly where - humanity passed a kind of tipping point where the effect of our ability to increase the efficiency of our own labor changed.

Up until then, humans were still pretty much in a struggle for bare survival. As a species we had very little in the way of luxury. Inventing new tools was downright essential to enable more people to actually live full lives without dying of starvation or disease or exposure or whatever. A significant majority of the labor that most people did could be characterized as essential. Of course, no picture is perfect, and some forms of non-essential labor have been around a long time. You could argue we passed the tipping point as soon as we were able to make our labor efficient enough that human social groupings could support people who'd passed the age of practical reproductive ability. Or singers. Or, hell, prostitutes. All of which has been true for a long time.

But still, I think it's reasonable to say this effect became far far more obvious and significant in the last few hundred years. We became so efficient at the work of growing food and building shelter and protecting ourselves from predators and so forth that it took substantially less than the total amount of potential work that all human beings could do in order to support the basic necessities of life for all human beings. We didn't need all 500 million people on Earth, or whatever it was at that time - or, if you want to simplify to a single country, let's say the 5 million people in England, or whatever it was - to actually support the bare necessities of life for those 5 million people.

We had, in effect, a labor surplus - we had more potential labor than we actually, strictly speaking, needed.

Not coincidentally, this is the point in history at which the Luddite argument first emerged. When you're a stone age hunter you're probably not really going to be worried about the consequences of some bright spark inventing the wheel; it's not as if you're going to wonder what you're going to do now your 'job' of transporting things around agonizingly slowly and inefficiently has disappeared. It's still pretty painfully obvious on any scale that there's going to be Other Stuff For You To Do. Finding Stuff To Do is not going to be a problem.

It's when we hit this situation of a labor surplus that it can start to look like a problem. Because you can look around and think, hey, there isn't actually anything else that really needs doing, so...what now? The steam hammer came along and took my job! And on a micro scale, you're often actually right. New inventions do take away people's jobs.

On a macro scale, though, you're wrong, in general. Why? Because of what human societies seem to do when they hit the labor surplus case.

It's very interesting, and it's where the early-20th-century American framing of the Luddite argument - no-one will have to work so hard any more! - goes slightly wrong. Because instead of adjusting things so that each person has less labor to do, it seems like what human societies end up doing is inventing more labor.

We come up with utterly non-essential things to do, and have people do those instead. And we call them 'work'. But really, they aren't.

Most jobs aren't really jobs. They're occupations. Pastimes. Professions, perhaps. So really, the future that the American robot utopians predicted has come to pass, but by stealth. Most of us do things that anyone from the past would consider recreational pursuits, but call them 'jobs'.

For an entirely random and not-at-all-pointed example, let's look at advertising, or TV. If you look at it in a certain way, people who 'work' in those fields aren't really working at all. No-one in the entire world needs the Big Bang Theory to exist. There is no fundamental reason why hundreds of people should be paid to write, act out, film, produce, edit, promote and transmit that television show. It's entirely non-essential labor, and what really is the difference, at a fundamental level, between 'non-essential labor' and 'recreational activity'? It's a tricky hair to split.

In case it's not clear, I don't really think this is a bad thing. I think it's an interesting thing - the way people don't seem wired to accept a world in which they 'don't work', so instead of 'not working', we play little mind games with ourselves in order to call utterly frivolous pursuits 'work', so we can have people spend their whole time doing stuff that isn't really necessary but not get mad at them for 'not working'. Really, we're all living in the future and have been for decades, centuries: the robots came and took almost all the really essential labor over years ago. It takes a microscopic percentage of humanity to grow our food and build our houses. All the stuff the rest of us do is just fun and games, and we've built a wonderfully intricate Heath Robinson device of a society to misrepresent it as 'work' so we don't feel like we're slacking off. Aren't people amazing?

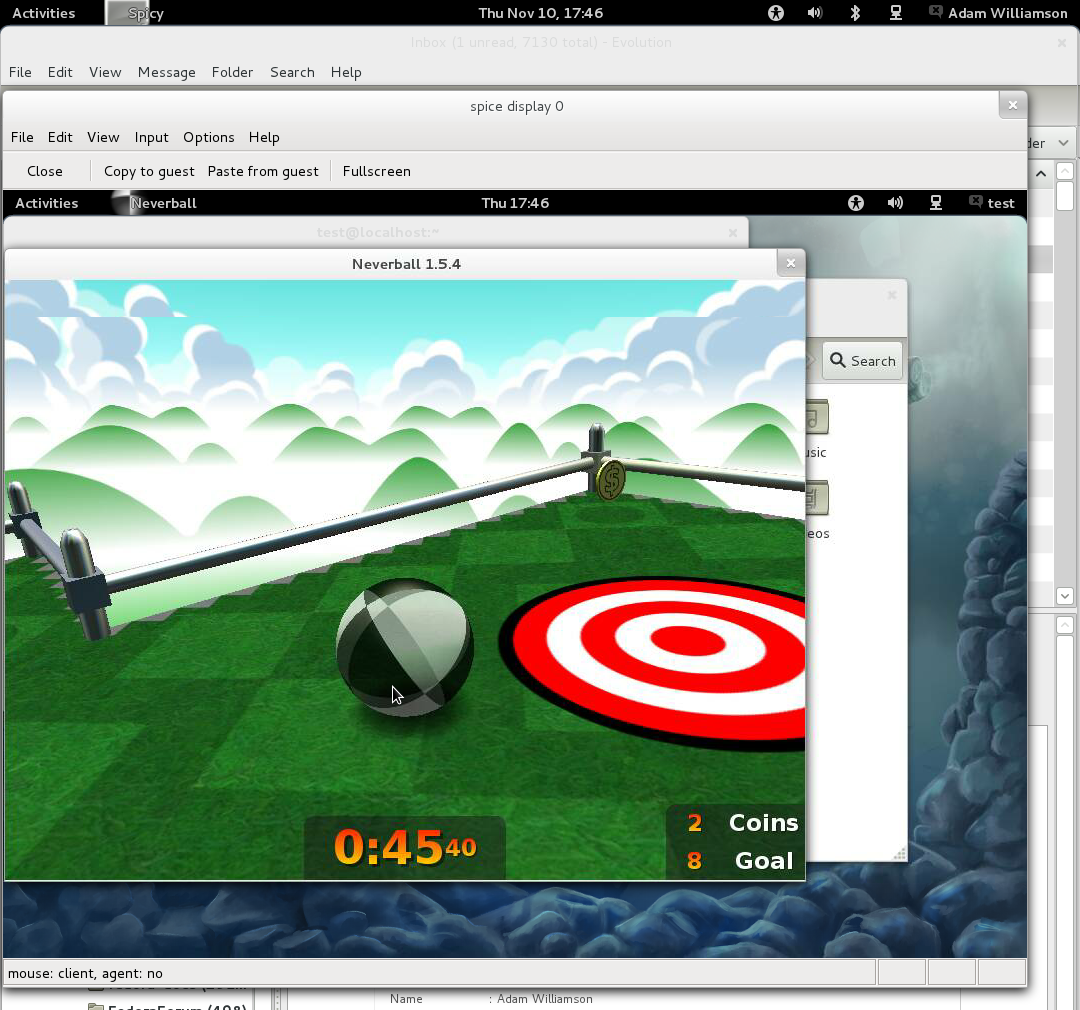

That's Neverball, running inside GNOME Shell, running in a Fedora 17 VM, on a Fedora 17 host. Unstable enough for ya?!

Impressively, it's just about playable, though the graphics are bit messed up, there's some flickering that shouldn't happen. Looks like about 8fps. This is using the current F17 kernel rebuilt with debugging disabled on both guest and host - it's a lot slower with the

'stock' F17 kernel, as that has debugging enabled.

F17 more or less works at the moment, probably because no-one's changed much vs. F16, though PolicyKit seems to be broken; I'm looking into that.

That's Neverball, running inside GNOME Shell, running in a Fedora 17 VM, on a Fedora 17 host. Unstable enough for ya?!

Impressively, it's just about playable, though the graphics are bit messed up, there's some flickering that shouldn't happen. Looks like about 8fps. This is using the current F17 kernel rebuilt with debugging disabled on both guest and host - it's a lot slower with the

'stock' F17 kernel, as that has debugging enabled.

F17 more or less works at the moment, probably because no-one's changed much vs. F16, though PolicyKit seems to be broken; I'm looking into that. As well as contributing one of the vital F16 fixes at one of the earlier 'last minutes' in the process, ajax has only been and gone and got GNOME Shell running in a KVM. Oh, hell yes.

That's Shell running on software OpenGL, llvmpipe specifically. Still very early, but should be committed to Rawhide soon and therefore available in Fedora 17. Amazing work. As well as making it work in VMs, this should allow Shell to work on just about any system with a reasonable amount of CPU power, even if it doesn't have hardware accelerated 3D. Almost no need for fallback mode any more!

As well as contributing one of the vital F16 fixes at one of the earlier 'last minutes' in the process, ajax has only been and gone and got GNOME Shell running in a KVM. Oh, hell yes.

That's Shell running on software OpenGL, llvmpipe specifically. Still very early, but should be committed to Rawhide soon and therefore available in Fedora 17. Amazing work. As well as making it work in VMs, this should allow Shell to work on just about any system with a reasonable amount of CPU power, even if it doesn't have hardware accelerated 3D. Almost no need for fallback mode any more!